An MFA Taught Me to Give Up

And that's a good thing.

I just earned an MFA in creative writing.

One day, I'll catalog every lesson I gleaned from the two-year program. For now, I want to focus on what I think was one of the most important ones: giving up.

Devoting two years to the art of writing requires perseverance, yes. But giving up can be the difference between Sisyphean agony or thrice parading your completed works around the walls of Troy in victory.

I started with the former.

The Goal

Giving up requires a goal to abandon in the first place.

Mine?

I wanted to write genre fiction—namely high fantasy and science fiction novels.

An obsession with Warcraft III, World of Warcraft, and Battlestar Galactica dominated my teenage years. I read Tolkein's The Lord of the Rings trilogy and numerous short stories by Harry Turtledove. It's no surprise, then, that I wanted to create my own similar fantasy worlds and futuristic locales.

But by college, I "matured" out of enjoying fiction. My plunge into nonfiction in pursuit of a history degree gave me the impression that fiction was for children. After all, wasn't fiction just Harry Potter and The Hunger Games anyway?

Then I read George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire.

No other books made me stay up until 2:30 am flipping through pages like the meaning of life was just one more sentence away. Creating something just like it—at least in tone, scale, and complexity—became my new mission in life.

Reality

When I finally had stable employment after college (and it took a while), I jumped headlong into creative writing.

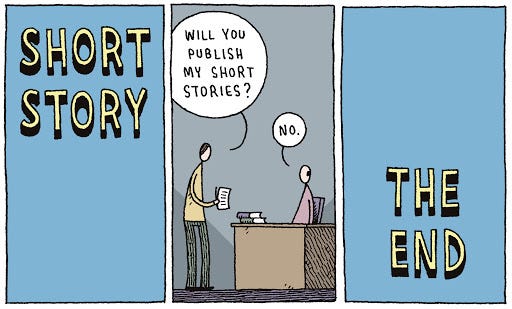

Seeing short stories as worthless, I jumped straight into novels. From 2015-2020, I wrote two novels that failed to find representation. In 2021, I started a third but kept feeling like I was making no progress craft-wise. I was utterly lost and creatively broken. I had no idea what to do. All I knew is that no matter how many writing books I read or podcasts I listened to, I never got better.

I hoped an MFA would give me what I needed: the ability to write good fantasy and science fiction.

I told one of my professors about my novelistic ambitions, and he pressed me to write short stories. I was initially hesitant. Novels are the currency of writing careers, not short stories. Per author and Columbia University writing instructor Lincoln Michel:

Publishing runs on novels. At least when it comes to fiction, novels are what agents want to hear about, what editors want to look at, and—with a few exceptions—what readers want to buy.

But I listened to my professor, and gave short stories a try.

Resistance

You'd think two of the first four short stories I wrote in the program getting published (Headless Angels and The Sculptor, but who's counting) would teach me something. Perhaps that I should pursue the short story form but also lean into stranger and more literary modes.

Alas, I ignored the evidence.

My goal was to write SFF novels. So that's what I was going to do.

I spent half my second semester on my Science Fiction Novel, and the other half on a smattering of short stories and microfiction.

I wrote a longer short story of 10,000 words that's forthcoming (I can't say much more). I tried merging form experimentation with fantasy elements (necromancy) and historical fiction (utilizing my fascination with World War I). The result was the story Necromancer of the Trenches.

The short stories were just a side thing, though. A passing fancy. Something to do in between edits of the more important project: my Science Fiction Novel. When I signed up for a novel writing workshop in January 2023, I thought I'd never be writing short stories again afterwards.

Nadir

The Science Fiction Novel was bad, folks!

I followed every rule a writer is supposed to follow for writing genre fiction. Yet the novel still wasn't good. Readers felt the novel was empty, formulaic, and sterile (they phrased all of this in an exceedingly polite manner).

I sat in Maine hotel room in a near catatonic state with one thought playing on repeat: should I give up genre fiction?

I couldn't write an effective science fiction novel despite, at that point, one full year of graduate study in creative writing. My pure genre fiction short stories never got published and were always my worst-received stories at workshops.

Worst of all, the criticism of my novel mirrored my own criticisms of contemporary SFF: that its largely devoid of anything interesting, literary, or even soulful.

Not only had I failed to write anything good, I'd actually written the very thing I've hated about SFF since my interest in the space reignited post-college.

This was the low point. I'd given up on two novels already. Should I give up on a third? And on genre fiction entirely?

Freedom

The more literary stories I wrote were easier to do and, ultimately, got published.

The crunchy genre fiction stories I wrote were painstaking to do and, ultimately, did not get published.

I wrote the successful short stories on a whim, having fun with the idea of writing for writing's sake, and exploring vulnerable and interesting topics. I went in with no expectations other than "let's do a piece that's below 1,000 words..." and I let each sentence write the next one.

I wrote the unsuccessful stories (including the novel) with a cumbersome top-down conceit that got in the way of the actual story.

For whatever reason, I can't approach genre fiction any other way than from the top down. There's numerous other issues, too. For example, fellow students and professors said my genre fiction dialogue was stilted, florid, and overblown.

What you want to write is not always what you're good at writing. I had long discussions about this with several professors.

I could labor tirelessly in the hopes of becoming an RC Cola George R.R. Martin, or I could attempt to build a more unique voice suited to my own abilities and interests. It's my opinion that the end result on the page will ultimately reveal where you should be and what you should be doing.

I'm not "giving up" genre fiction as a rule. I'll still try my hand at writing it here and there. But I found letting it go to be liberating and massively influential to my development as a writer. I feel like I'm writing the things I'm meant to be writing as opposed to writing the things I feel I should be writing.

I couldn't have reached these revelations without the MFA program. I'd be trapped writing failed novel after failed novel instead of experimenting, adapting, and growing.